When a consumer visits your website, any number of things can influence their decision to purchase and engage with your brand. There’s the typical factors, like product, pricing, and brand, but there are also psychological factors — factors hardwired into our brains that can play a major role in our decisions.

The following eight principles are proven to affect us immensely. Here’s what they are and how you can apply them to grow your online store.

Reciprocity Principle

We return the favor; when someone treats us positively, we give back similar treatment.

This psychological principle is old school. It goes as far back in time as an old dude from 1792 BC called Hammurabi, known for his code and one of his famous laws: “an eye for an eye.” Reciprocity is often applied to social rules, mostly because it’s in our very nature. Think “treat others the way you want to be treated,” or “you reap what you sow,” or “what goes around comes around” — these phrases sum up what reciprocity is all about.

Putting It to Work

Reciprocity is extremely well-known for its marketing influence — some would say it’s the bedrock for promotions, discounts, and gifts. You’re offering a discounted benefit to the customer who returns the favor with a purchase.

But it’s a matter of maximizing the principle. A general promotion is fine, you’ll likely get some customers biting, but a personalized and unexpected one is likely to boost effectiveness significantly.

A study on tipping by Cornell University illustrates how those two things — unexpectedness and personalization — can enhance the power of reciprocity. When presented with mints after receiving the bill, customers tipped more than those that didn’t receive anything. Boom, something unexpected — a small gift of a mint — is reciprocated with a greater tip. And when customers personally interacted with the waiter or waitress upon receiving the gift, tips went up even further.

Do something similar — segment those awesome customers of yours, and shoot them an unexpected email with a personalized discount. Ideally they’ll respond the same way: happily surprised by your pleasant little promo, they’ll take advantage of the offer and buy.

The Foot-in-the-Door Technique

When a person agrees to a small request, they’re more likely to agree to a larger one afterwards.

A famous study in the 1960’s by Jonathan L. Freedman and Scott Fraser indicated how the foot-in-the-door technique can persuade people to behave a certain way. A team of psychologists called Californian housewives, asking one group of them to answer some questions on household items they use. Three days later, they called those housewives again, asking if they could send a few men into their house to inspect cupboards and storage spaces for 2 hours in an effort to catalog all their house products. Instead of asking the household item question, a separate group of housewives were immediately asked about the inspection. Of the two groups, those asked about household items in a lead up to the inspection were far, far more likely to allow an inspection.

More recently, foot-in-the-door tactics have been tested at bars. Some participants were asked to sign a petition against drunk driving, given an informational pamphlet, and asked to get a taxi if they became intoxicated. Others were left alone. Repeated over the course of six weeks, the experiment showed that a significant amount of the anti-drink-and-drive, petition-signing participants called taxis instead of driving impaired.

Putting It to Work

The big, end-goal for a merchant in most cases is a sale, so implementing the foot-in-the-door technique is about getting the customer to act in a way that gradually leads them there. Look to that sales pipeline.

Whether it’s on your social sites or blog, entice the customer with engaging content — get them engaged with your brand. Then ask for an email address so you can send them more of that content (and promotions…). Heck, even ask them for a share once they’ve viewed it. The hope is that they follow through the pipeline with your “requests,” i.e. content and promotions, which eventually leads to a sale. Even after the customer makes a purchase, your foot is in the door to ask them for yet another request: a positive review that encourages even more potential customers.

Peer Pressure

We change how we behave to be more like others; if we don’t know how to behave, we copy others.

As social creatures, we modify our behavior to meet the expectations of our friends, family, peers, influencers, even strangers in unfamiliar environments. Whether consciously or not, the way we act is shaped by others, and we actively conform to those around us.

Putting It to Work

Influencers are important here. As you market your business, seek out industry influencers — those bloggers, content creators, and brand champions within your space — and work with them to introduce yourself to their audiences, ideally driving traffic and sales your way. The followers of those influencers identify with them in some way, whether it’s lifestyle or beliefs, so if the influencer has a positive outlook on you, those followers are likely to adopt the same feeling toward you.

Social proof is a perfect representation of how social pressures influence behavior — positive or negative, it can have significant impact on how your business is perceived. The best example of social proof comes in the form of — you guessed it — reviews. Consumers look to online reviews for the go-ahead to buy products; they don’t know how they want to behave (i.e. if they want to buy), so they’re looking to others’ experiences for information on how they should act. Encouraging positive reviews after gaining a happy customer should be a ritual.

Mere Exposure Effect

We prefer things that we’re more familiar with.

Introducing participants to a variety of stimuli, like words, pictures, and figures, R.B. Zajonc in the 1960’s discovered that repeated exposure to the stimulus, even if negative or fear-inducing, increases the chance that a participant will prefer it over a lesser-known alternative.

Mere exposure has also been tested in consumer products. Researchers found that positive feelings for products grew with how familiar they appeared. Products shaped in familiar styles, like an aluminum can or Coke bottle for instance, were preferred over an alternative, less familiar shape. When presented completely made up shapes that were alien, the participants always preferred the shape that they were more frequently exposed to.

Putting It to Work

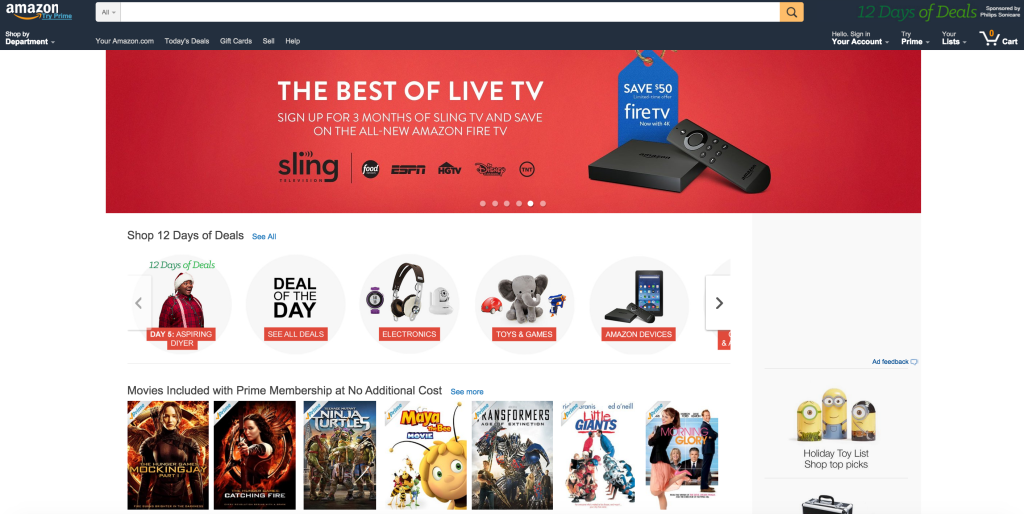

If you want to successfully get sales, step #1 is ensuring that customers are familiar with your website. An outlandish, edgy site design won’t do you any favors here; use proven layouts that customers are accustomed to, like a style similar to Amazon’s for instance — big banner, followed by popular products or deals, and then other products or categories.

The goal is to make that potential customer’s first experience as familiar as possible so they don’t bounce. The way they travel your website needs to come easy to them, else they’re liable to scatter thanks to that lack of familiarity.

The mere exposure effect can affect your consumer post-sale, too. Familiarity breeds loyalty — when a customer makes their first purchase, foster their loyalty by introducing other personalized deals to them. Motivate them to follow you on your social feeds, and stay in contact with them to build engagement and familiarity as a result.

That said, do be sure you not to overdo it. Annoying, irrelevant, and incessant marketing messages can definitely backfire, taking the mere exposure effect and turning it into the over exposure effect.

The Decoy Effect

We change our preference between two options when presented with a third option that’s completely inferior to one option, but somewhat inferior to the other.

This mental phenomenon is a proven principle, it’s been applied to prices and more important things like general elections. Plenty of businesses make good work of this effect, as it’s perfect for nudging a consumer toward a more expensive product, rather than a cheap one. But let’s get into how it works in a business scenario.

Putting It to Work

Here’s an example of how the decoy effect operates. Let’s say we have two MP3 players for sale (I guess today is throwback Thursday).

Source: Paul Olyslager

Many consumers are spooked by A thanks to the fact that it’s $100 more than B for just 10 GB. But some consumers might really want that storage. It’s a matter of preference: some will go for the increased storage (A), others will go for the cheaper price (B).

That said, we would prefer that they buy A, the more expensive of the two. Then enters the decoy, MP3 Player C, to work its psychological magic, pushing a customer toward MP3 Player A, the more pricey option.

MP3 Player C is more expensive than the others — completely inferior in that aspect — but has more storage than B and less than A, making it somewhat inferior to the other options.

Why would anyone ever want MP3 Player C? With A, they can pay $50 less for a more storage. That’s the exact line of thinking for many consumers. MP3 Player C, the decoy, is placed deliberately to push B out of the picture and drive sales of A. You see this everywhere, from bottles of alcohol to popcorn sizes at the movies.

It’s possible to apply this to your store, even if you aren’t dealing with the same product in different sizes. Set up very similar products, like the products in a specific category, near one another and pick out one of the products — maybe a slow-seller or a high-selling product whose demand could withstand a hit — to be the decoy. As you set products to be decoys and attach prices to them, be sure to test whether or not it’s working by checking out the sales history of the products affected by the decoy effect.

The Endowment Effect

We’re very unwilling to trade or sell something that we own, even if we’ve possessed it for a short period of time. When we do have to trade or sell it, we demand more than what it’s actually worth.

There have been several studies on this psychological principle. During a class in 1980, a college professor at Cornell University offered half of his students coffee mugs, giving the other half nothing. He then encouraged the mug owners to sell the brews to their coffee-less peers. Very little trading occurred. Even after owning the coffee mugs for a minuscule period of time, the students valued their newly-owned belongings higher than what non-owners were willing to pay for them.

The owners could’ve easily sold their mugs for a quick buck that they didn’t have before walking through the class door. But they didn’t. Long story short, the mug owners’ potential loss was larger than the non-owner’s gain, so they resisted a sale.

Putting It to Work

The endowment effect is a little trickier to implement in your online store because there’s no loss of ownership to avoid when a potential customer visits your site; they haven’t purchase anything yet. Instead, use the principle to retain those current customers. When a customer purchases a product, grow their ownership of it and your brand. Encourage them to provide feedback, reviews, and involve themselves with your brand on social media.

The Framing Effect

People react to a particular choice depending on how it’s presented: as a loss or a gain.

The framing effect is extremely powerful — mere manipulation of words can present a mere statement in an entirely different light, one that elicits a positive or negative reaction depending on who’s doing the framing.

For example, a study by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman chose the topic of a life and death situation to find out how framing changes decisions. Here’s how it went down: participants had to choose between two treatments for 600 disease-ridden, doomed people. Treatment A meant 400 people would die, while Treatment B meant a 33% chance nobody would die and a 66% chance that everyone would die.

Both treatments were then framed in positive and negative lights:

| Framing | Treatment A | Treatment B |

|---|---|---|

| Positive | Saves 200 lives. | A 33% chance of saving all 600 people, 66% possibility of saving no one. |

| Negative | 400 people will die. | A 33% chance that no people will die, 66% possibility that all 600 will die. |

When presented in a positive light, 72% of respondents chose Treatment A. Who doesn’t want to save 200 lives? But when Treatment A was presented negatively, with 400 dead, the respondents flocked to Treatment B, regardless of Treatment A’s better chance to save those poor, disease-ridden people.

This effect comes down to risk. The way something’s presented, as a loss or a gain, is the crux of how the framing effect operates, and people are far more inclined to go with the gain.

Putting It to Work

This is a classic, and one many businesses have been eager to manipulate, especially when it comes to pricing.

Bundling products is an opportunity to apply framing. Let’s say you’re trying to get rid of slow-selling Product A that costs $12 by bundling it with high-selling Product B that costs $20. You plan on slashing the price of the slow-seller by 50%, bringing it down to $6, but want to keep the regular price of the high performer. So, combining the two costs, you decide to price the bundle at $26.

A customer comes to your site and sees two attractive products: the high-selling Product B and your newly-created bundle. They don’t like the idea of paying $6 more for Product A, which they aren’t interested in, just to get Product B. To encourage them to purchase the bundle, start framing. Slap on a label to the bundle highlighting the fact that it’s a deal — a nearly 20% discount! Ideally, framing it this way stresses that it’s a deal — it’s a gain, not a loss of $6 — prompting a customer to act, and getting both items off the shelf.

Loss Aversion

We strongly prefer avoiding losses; the mental impact of a loss is far more powerful than that of an equal gain.

Many of the previous principles really boil down to this. We just don’t like loss, even if it’s cancelled out by an equal gain.

Why do we human beings feel this way? Surprisingly, many claim that it has little to do with wealth or emotional attachment. The reason we do this, from an evolutionary standpoint, is because it’s simply too risky to give up something. Call it the struggle of survival when we were cave people or a general fear of loss, but our brains are hardwired to avoid risk, even if the proposed tradeoff is equal in value. Some studies even claim that the impact of loss is nearly twice as strong as that felt from a gain.

Putting It to Work

A lot of times, potential customers can’t quite trust an e-retailer enough to click “buy.” They don’t get to experience the product in person, they’re relying on reviews, and they just don’t have enough trust to convert: they don’t see a gain in a purchase, they see a potential loss.

A solid way of remedying this that’s often employed during high-selling seasons like the holidays, is offering free returns or full refunds. Doing so conveys the fact that you’re confident in your ability to deliver, and it reduces the customer’s anxiety toward potentially losing money if the purchase doesn’t live up to expectations.

But if you’re looking to capitalize on loss aversion instead of reducing it, look no further than fear of missing out (FOMO). Just as we don’t like to lose a belonging, we don’t like to lose out an opportunity. Introduce limited time offers to reward your most engaged customers and spur anyone others to buy. Flash sales — sales that are completely unexpected and limited in time — also do a terrific job seizing on FOMO.

Photo: Flickr, dierk schaefer